The use of photography in the French press

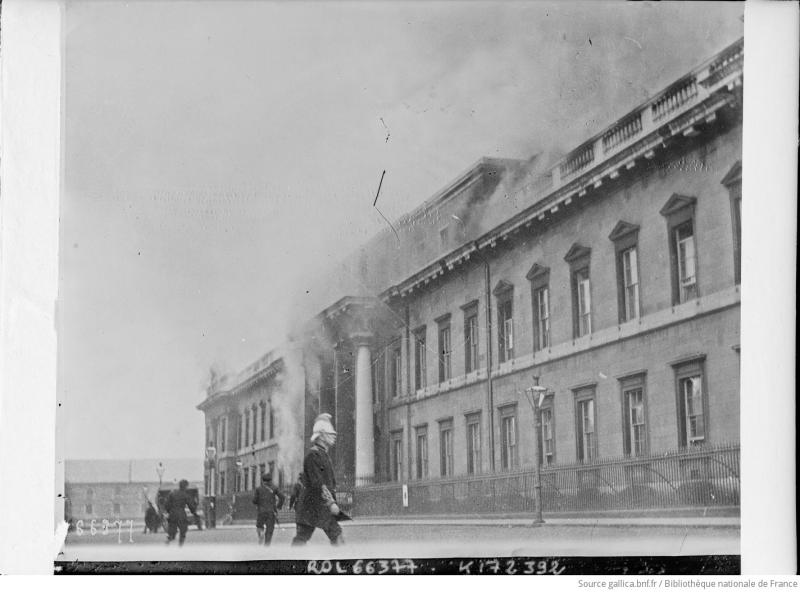

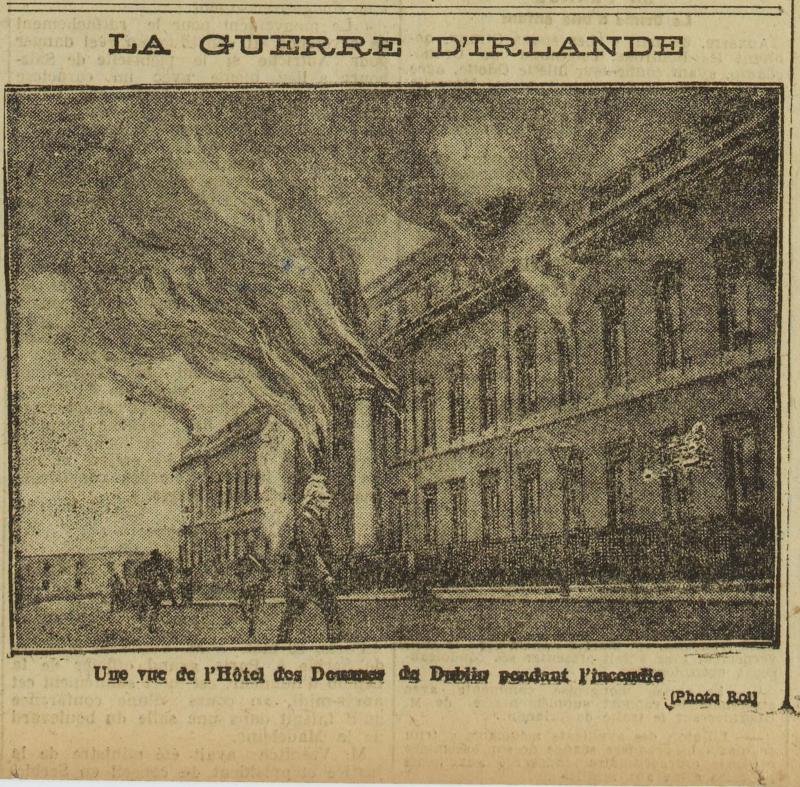

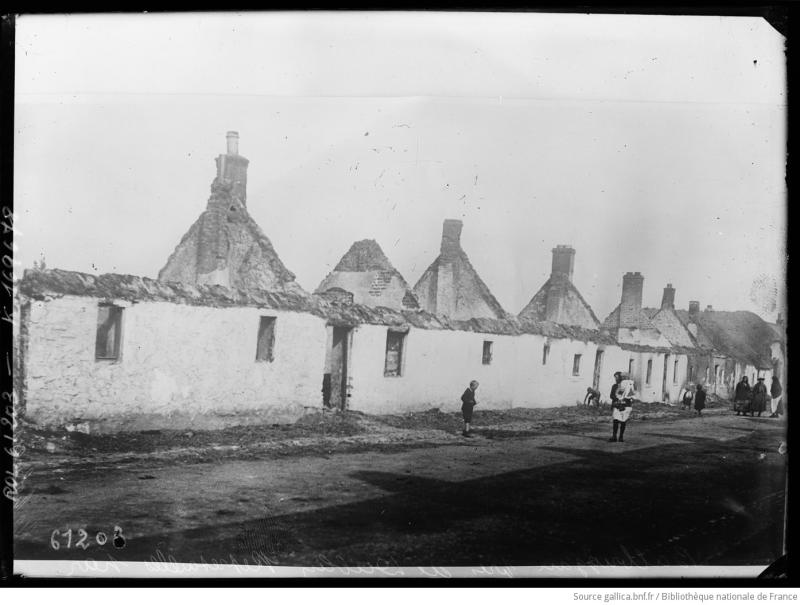

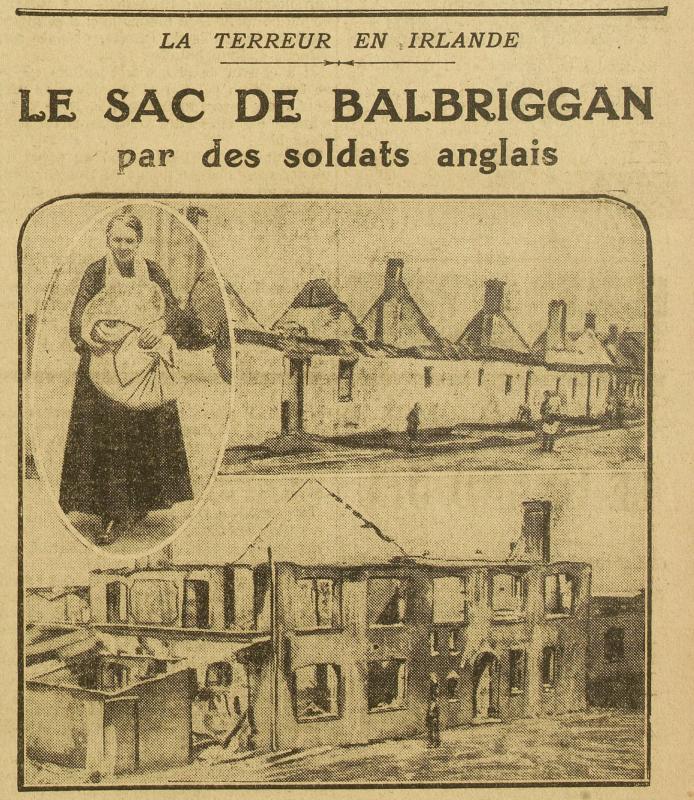

Press photography was still a fledgling art during much of the Irish Revolution. Photos were published widely as engravings due to the challenges of printing the image alongside the text. The example below shows the original press image of the fire at the Customs House in Dublin alongside its engraving which appeared in La Dépêche on 29 May 1921. When a photograph appeared in a newspaper, it usually appeared on the front page in order to decorate the text rather than as a source of information in its own right. See the examples below relating to the reprisals in Balbriggan. The improvements brought to the Belinograph in 1921 – Édouard Belin's 1907 invention that made the remote transmission of photographs possible – now allowed for faster transmission of images. Consequently, the use of original photographs became more frequent during the civil war.

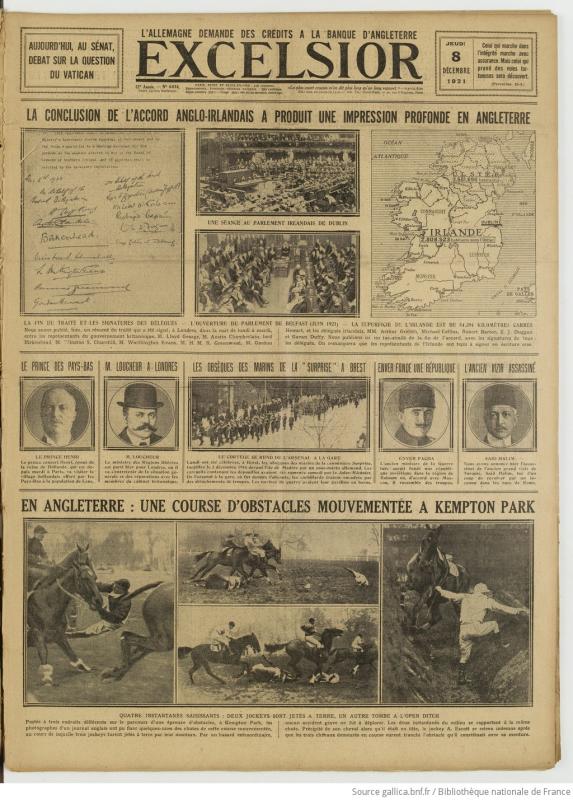

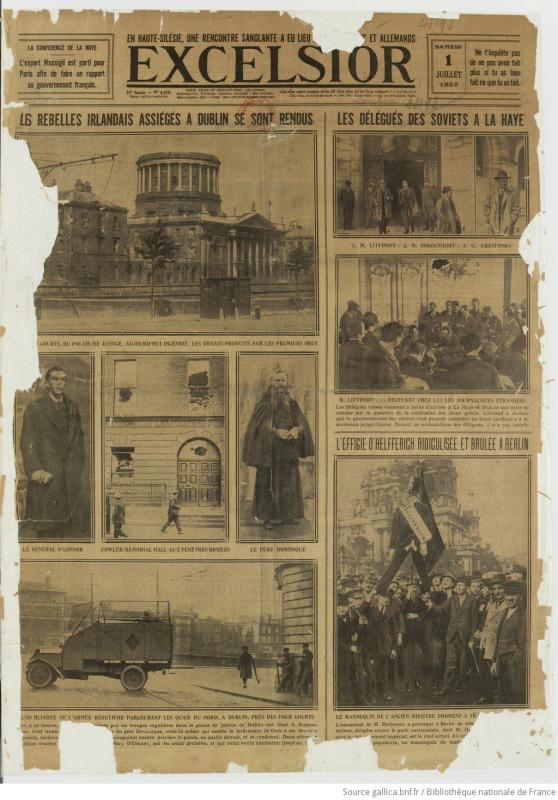

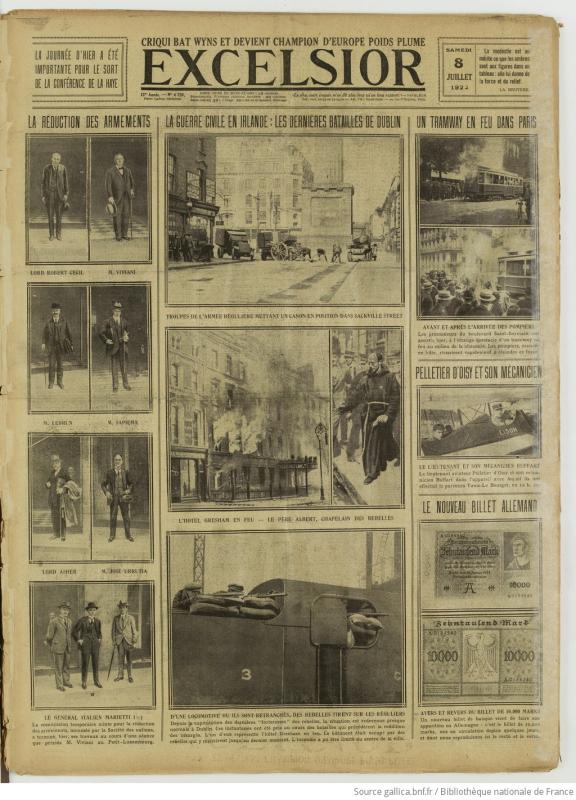

Even if the use of photographs in general newspapers could be sporadic, a more in-depth form of photojournalism emerged with the development of illustrated newspapers. In 1916, Le Miroir published images taken during the Easter Rising, including a striking photograph of Constance Markievicz on board a police truck. A detailed feature on the Irish question also appeared in La Science et la vie on 1 June 1916. An article by Charles Rabot was illustrated with engraved portraits of the leaders of the rising, including Markievicz, Connolly, and Clarke, alongside other key political figures like Redmond and Carson, and a map of the island. Perhaps the most prominent example is the illustrated newspaper, Excelsior, based in Paris, which regularly published photographs of the revolution in Ireland, including several front-page reports. See the examples below of the announcement of the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty in December 1921 and of the Battle of Dublin between pro- and anti-treaty forces of the IRA, which was the subject of several front-page reports during the first week of July 1922.

Nevertheless, there is a dual difficulty in studying many of these images. First of all, few, if any, of the images published in French newspapers mention the photographer’s name. The Gallica database, from which these images originate, lists the name of the press agency as the ‘author’ of the image, either Rol (1876-1905) or Meurisse (1909-1937). Further work will be required to determine, where possible, the name of the photographer and their story in Ireland. In some cases, this has already been done. The famous portrait of Michael Collins that appears in the Gallica database is also in the Keogh brothers’ photographic collection held by the National Library of Ireland (NLI). We can therefore infer that the Keogh brothers took the original image and the Rol Agency purchased it later.

Another example is the engraved portrait of Arthur Griffith used by Excelsior to announce his death. The original oval photograph appears in the Joseph Cashman Collection held in the RTÉ Archives. Cashman was a photographer from Cork who took many iconic images from the Irish revolutionary period. Many of these images appeared in newspapers worldwide – often without crediting him.

This brings us to our second difficulty. As Susan Sontag explains in Regarding the Pain of Others (2003), ‘photographs objectify: they turn an event or a person into something that can be possessed’. The global economy of photography, press agencies, and newspapers convert the reality presented in the image into an object that can be owned, disseminated, and consumed. This means that viewers and institutions like the newspapers mentioned above can ‘own’ the suffering of others without experiencing it or assuming any responsibility towards them – even in the creation of this database, the images have become objects.

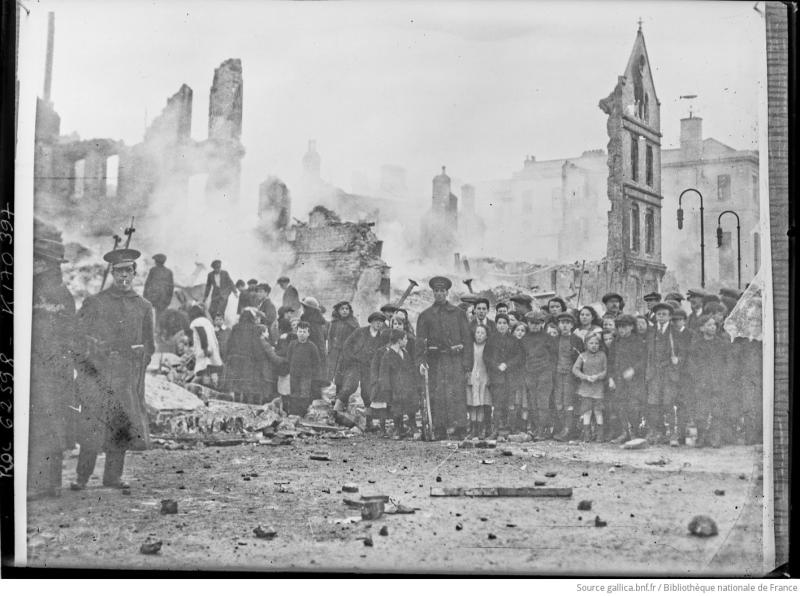

Of course, the narrative and context of the image can provide the viewer with meaning, particularly in the case of press photography when the image is accompanied by an article. Efforts have been made to provide a contextual understanding of the photos through the history of French reporting and photography presented above, as well as the timeline and biographies of some key figures that follow. However, to use Sontag’s words, photography in itself does not provide understanding; ‘Narratives can make us understand. Photographs do something else: they haunt us.’

A narrative can tell a story of cause and effect, of motivations, and of consequences. The power of the image is not the same as the text. Many of the images in this database show people in various states of suffering and distress, even death, following well-known events. Take, for example, the image of the family after the sacking of Balbriggan, or that of the citizens of Cork after their city was burned. Yet, when we look at an image, we do not experience the event itself, but rather a static representation. The power of photography therefore lies in its ability to make us feel rather than in what it helps us to know or understand. Perhaps images are, as Sontag postulates, ‘emblems’, but emblems that have a vital function: ‘The images say: This is what human beings are capable of doing – may volunteer to do, enthusiastically, self-righteously. Don’t forget.’