The history of the Irish revolutionary period in the French press

If Ireland and France maintained a close relationship since the unsuccessful expedition by General Hoche to help the ‘United Irishmen’ in 1796, the first significant French publications about Ireland date from the mid and late 19th century. These writings, often the works of authors who had traveled to Ireland, tend to comment on the social and political conditions of the island. Among the most notable works is Gustave de Beaumont’s L’Irlande sociale, politique et religieuse (1839). De Beaumont’s work was a great success and was reissued eight times during the nineteenth century. Other significant publications of the period include Cardinal Perraud’s study of socio-economic conditions in Ireland after the Great Famine, Études sur l’Irlande contemporaine (1862).

The Irish Revolution in the French press

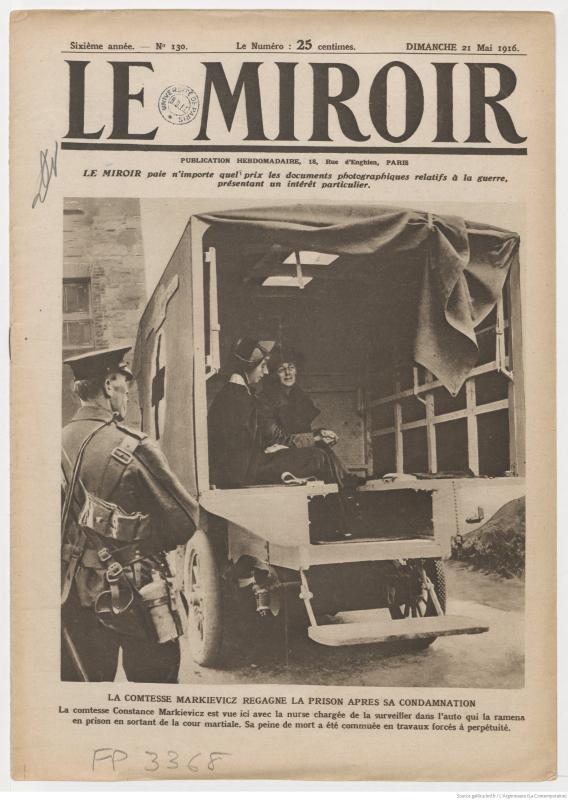

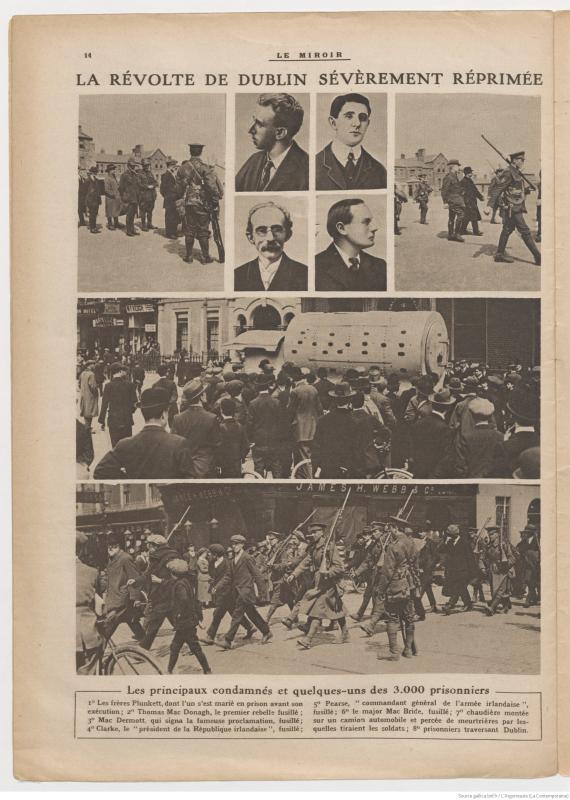

From the beginning of the 20th century, events in Ireland begin to receive significant coverage in the French press. Coinciding with the First World War, the revolution in Ireland came to capture the imagination of the French public with reports of violence and fighting in Ireland often appearing on the front pages of French newspapers. While revolution had been brewing in Ireland for some time, it was not until the Easter Rising in 1916 that Ireland properly entered the consciousness of the French public.

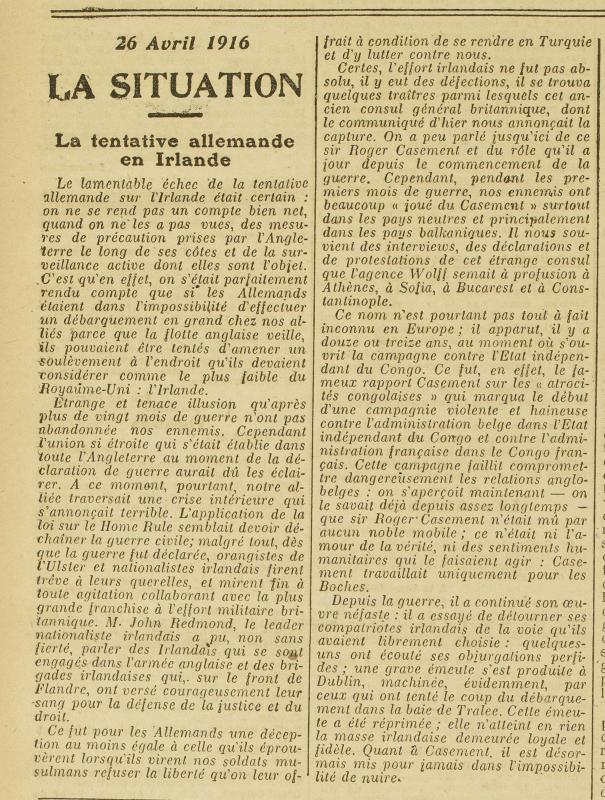

Many publications commented on the timing of the Rising at a crucial moment in the First World War. Various newspapers blamed the Irish revolutionaries for conspiring with Germany. The fighting in Dublin covered the front page of Paris-Midi throughout the week of the uprising. An article from 26 April 1916 stated that ‘il faut tout l’infatuation allemande pour avoir pu compter sur un mouvement favorable en Irlande’ [it took the height of German infatuation to have been able to count on a favourable movement in Ireland]. Similarly, Jean Herbette, writing in L’Écho de France on 27 April 1916, suggested that some of the Irish insurgents were funded by the Germans: ‘Il y a évidemment un petit nombre d’individus dévoyés, et de traîtres payés par l’Allemagne, qui cherchent à empoissonner la nation irlandaise’ [There is obviously a small number of deviants and traitors paid by Germany who seek to poison the Irish nation].

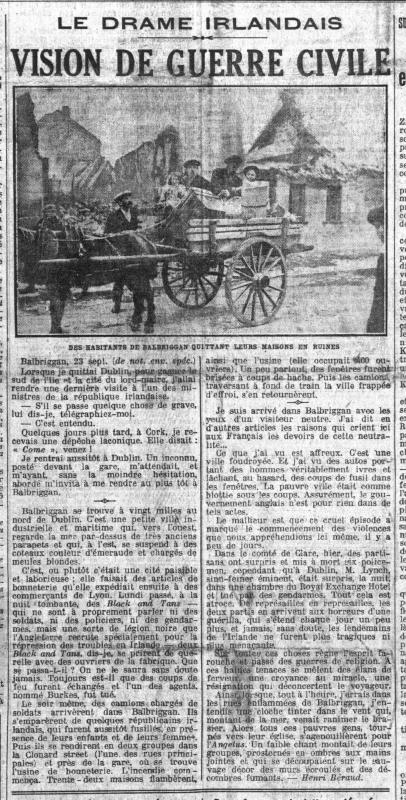

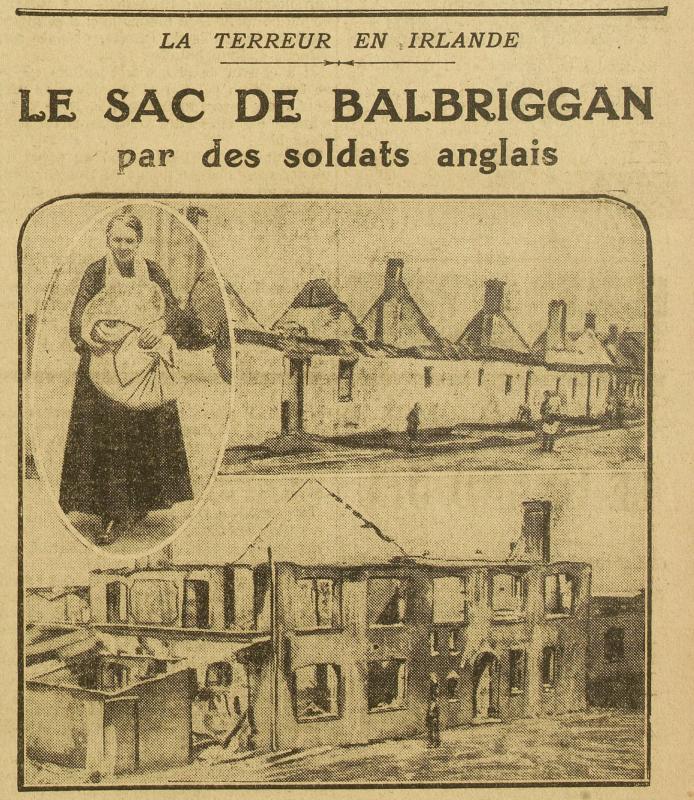

The years following the Rising are marked by a relative silence on Ireland in the French press, though several newspapers reported on the conscription crisis in 1918. However, the outbreak of the War of Independence in 1919 rekindled journalistic interest in Ireland. Throughout the guerrilla phases of the war of independence, the French daily newspapers reported on ongoing events in Ireland. The French journalist Henri Béraud, working for Le Petit Parisien, travelled to Balbriggan following the reprisals carried out by the ‘Black and Tans’ on 28 September 1920. Béraud’s reporting was accompanied by a photograph of a family fleeing from their ruined home. Even though Béraud’s article was front page news, his choice of vocabulary shows the challenges in documenting the conflict. Not knowing perhaps how to characterise the conflict between British forces and a state disputing its inclusion within the United Kingdom, Béraud chose, like other journalists in French publications, to refer to the conflict as a ‘civil war’. There was also a trend in the French press to dub all Irish republicans as ‘Sinn Féiners’, regardless of their affiliation with the political party.

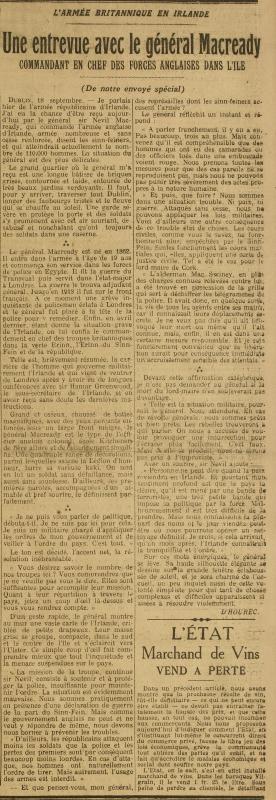

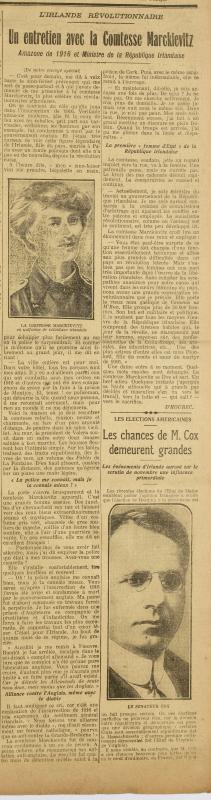

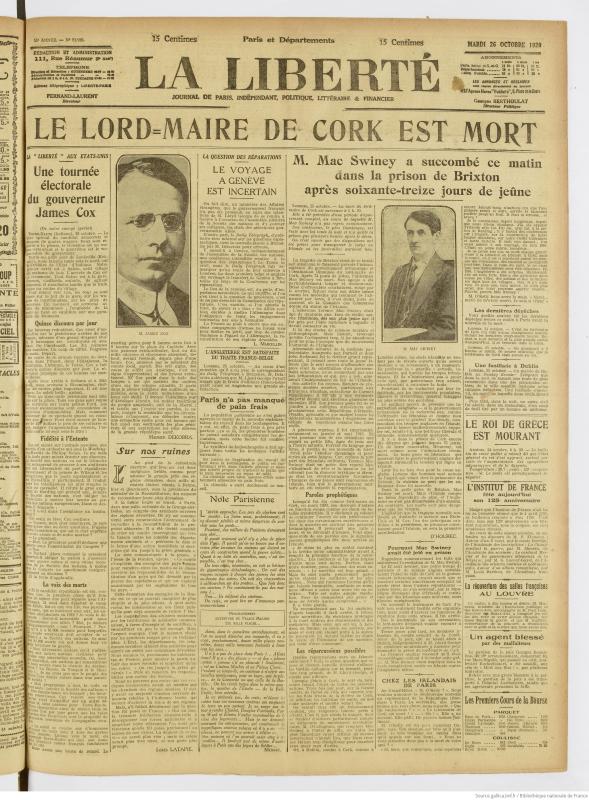

Journalist Joseph Kessel, later a member of the Académie française, was also present at Balbriggan. Kessel, who wrote for La Liberté under the pseudonym ‘D’Hourec’, relocated to Ireland to cover the war. His writings from this period (19 articles in total) cover topics ranging from the aforementioned reprisals at Balbriggan and the hunger strike and death of Terence MacSwiney in 1920 to the reaction of the English public to the war in Ireland and interviews with key figures, including General Macready and even a clandestine meeting with Countess Markievicz.

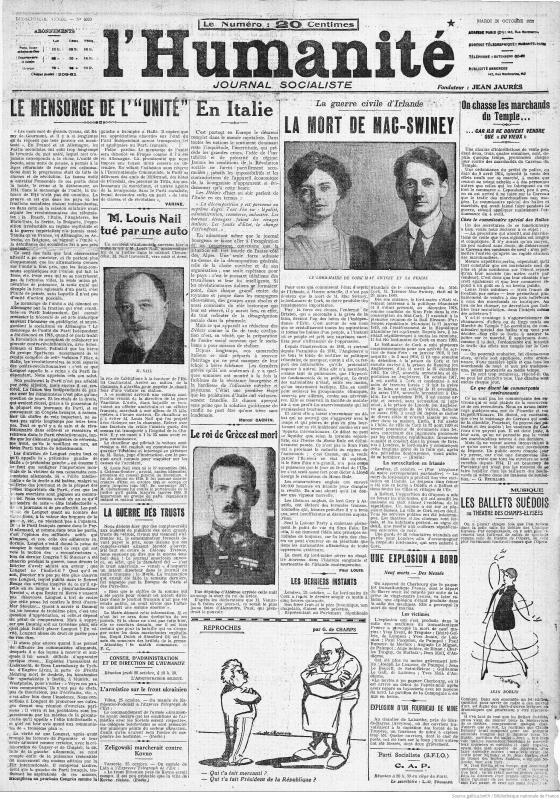

However, it was the hunger strike of Terence MacSwiney that brought the Irish situation to world attention, giving him a principal place in the French headlines. A poet, playwright, and the elected Lord Mayor of Cork, MacSwiney was arrested by English soldiers on 12 August 1920, accused of possessing seditious material. He was interned in Brixton prison where he went on hunger strike. Numerous French publications covered MacSwiney’s arrest, including Le Journal and Le Matin. Press coverage multiplied as MacSwiney’s hunger strike progressed, with updates appearing almost daily over the last few days of his life. Kessel went to Cork to report on the public prayers for the Lord Mayor, noting ‘un souffle de désespoir’ [a breath of despair] spreading through the city. Announcements of his death on 25 October 1920 dominated the front pages and several reporters presented his death as a key moment for rallying the Irish people. Paul Louis, reporting for L’Humanité, claimed that ‘C’est autour de son nom que se cristalliseront toutes les aspirations et toutes les haines d’un peuple, à l’instant où ce peuple est prêt aux suprêmes sacrifices pour s’affranchir de l’oppression’ [All of the aspirations and all the hatreds of a people will crystallise around his name, at a moment when the people are ready for the supreme sacrifices required to free themselves from oppression].

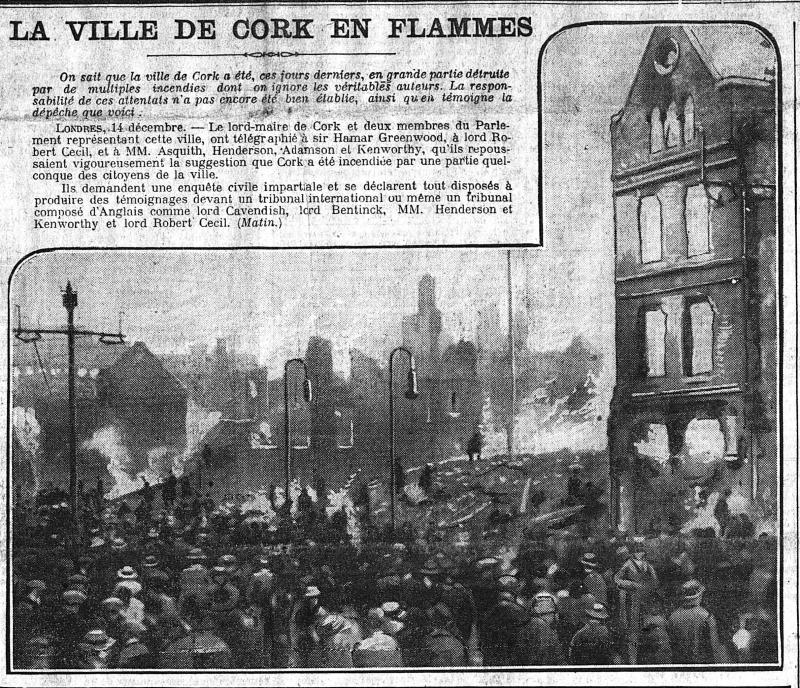

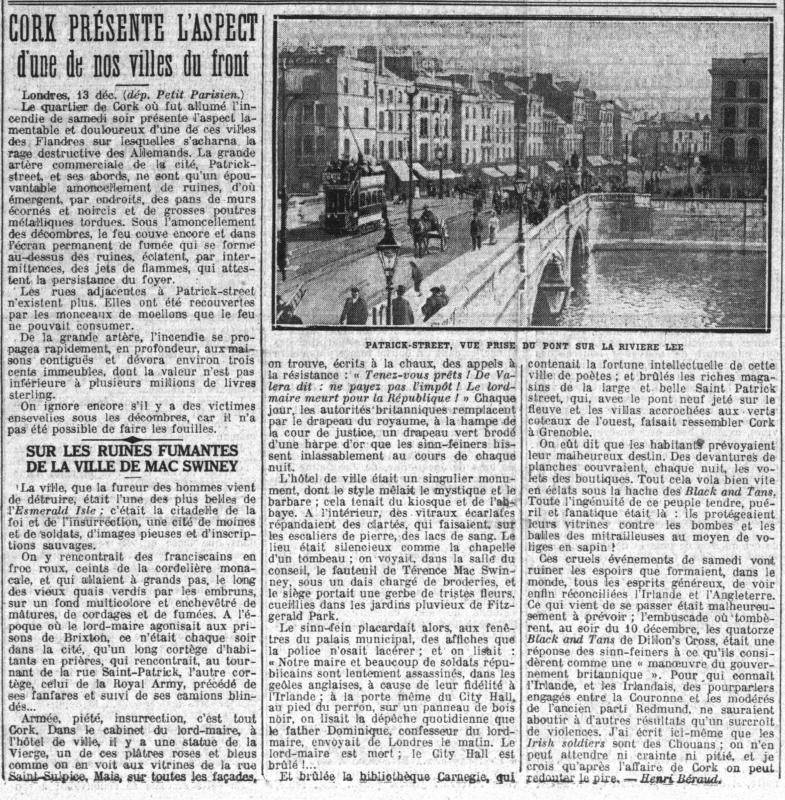

The war in Ireland continued to make headlines in France after MacSwiney’s death. However, unlike the reports on MacSwiney, reports on the assassinations of British intelligence officers on Bloody Sunday (November 21, 1920) were relegated to the international news sections at the back of the newspapers. On the other hand, the news of the Burning of Cork (11–12 December 1920) carried out by the auxiliary forces, the ‘Black and Tans’, in response to an IRA ambush on a British army patrol made headlines in French newspapers. Several reports evoked MacSwiney’s legacy when highlighting the destruction of his native city. For example, Henri Béraud’s article in Le Petit Parisien on 14 December 1920 bears the subtitle: ‘Sur les ruines fumantes de la ville de Mac Swiney’ [On the smoking ruins of MacSwiney’s town].

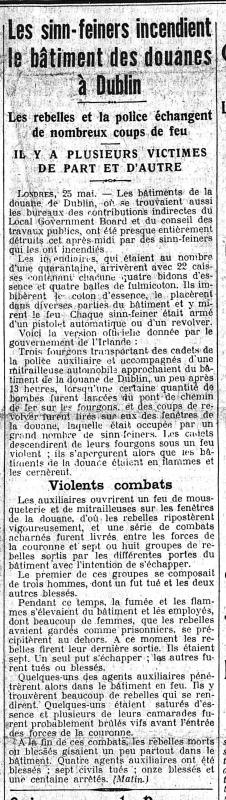

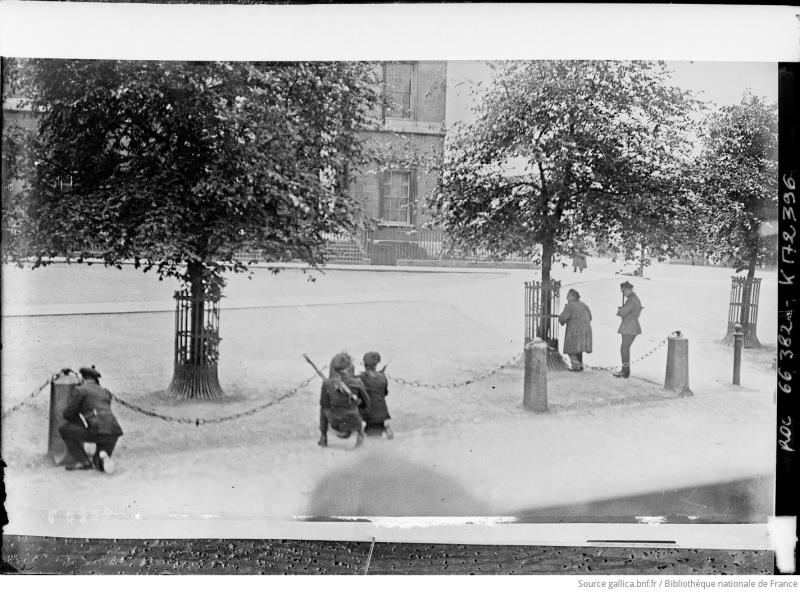

Violence continued through 1921, and French newspapers continued to publish reports and testimonies of the fighting. Le Petit Parisien referred to the first months of 1921 as ‘la série rouge’ [the red series] following the Crossbarry ambush in County Cork in March. Another event covered extensively in the French press was the fire at the Customs House in Dublin on 25 May 1921, which crippled British administration and was a symbolic victory for the IRA.